Ten symptoms of caregiver stress were listed in an Alzheimer’s Association newsletter with this caveat: Alzheimer’s caregivers frequently experience high levels of stress. It can be overwhelming to take care of a loved one with Alzheimer’s or other dementia, but too much stress can be harmful to both of you.

No kidding!

In any given day I deal with several of these, and I’m sure other caregivers do the same:

- Denial – Early on, I was convinced that if I kept trying to force Peter to remember things, to eat right, to get out more he’d at least maintain his status quo.

- Anger – Screams, like geysers ready to erupt, lurk just below the surface of my “looking for laughs” demeanor.

- Social withdrawal – Sometimes it takes too much effort do anything at all, much less be sociable.

- Anxiety – I’ve finally done what I should have done sooner: hired more help for Peter and for me. What a difference to have the house cleaned and tidied by a young lady who is energy personified, the garden maintained by a woman who knows first-hand what it’s like to be a caregiver, niggling tasks done by a handyman friend.

- Depression – Big mistake to think that I didn’t need anti-depressants. Hindsight and a meltdown proved me wrong.

- Exhaustion – I used to keep my house to a certain standard, not the same white-glove-test standard my mother used, but I kept the dust bunnies at bay, food in the fridge, cookie tin filled, laundry done. When I realized it had been weeks since I’d cleaned the bathroom or changed our sheets, I knew I needed more help. (see #4)

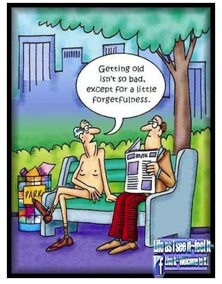

- Sleeplessness – Guilt wakes me in the wee hours, especially when I’ve crabbed at him for things he can’t help. Peter’s attention span is worse than a goldfish’s and he’ll ask the silliest things over and over. Within a few seconds he forgets I yelled and when I apologize he doesn’t know why.

- Irritability – No one has ever called me patient. Lately Peter has started reorganizing the pantry every few days, lining up jars and moving boxes so I can’t find anything. Most wives would be thrilled if their husbands undertook that task, but I’m an angry bumble bee.

- Lack of concentration – I used to be so organized, so tidy, but no more. My personal spaces are in the same sorry state as my mind.

- Health problems – Many times I wonder if his dementia has rubbed off on me. Am I losing control too? Is it stress, or am I destined to be a statistic as well?

I talked to my doctor. He did the basic tests and I passed. “Stress,” he said, “it’s stress. You’re doing fine, but take time for yourself, do what you can to alleviate stress.”

My mother always said, no matter how bad things may seem, there’s always someone who is worse off than you. I’m glad I’m not a goldfish.

2016 National Society of Newspaper Columnists’ contest finalist.